Is Alberta’s Minister of Forestry and Parks camouflaging the hunting of “problem” grizzly bears as a wildlife safety measure?

Back in June, Minister Todd Loewen, a renowned big game hunter and shareholder in a Valleyview-based outfitting business, signed a ministerial order that, to this retired biologist at least, appears to prioritize trophy killing ahead of science.

With no parliamentary debate, no vote in the legislative assembly and no formal consultation, Loewen’s ministerial order in one fell swoop allowed for grizzly bears to be killed in Alberta by sanctioned “responders.” These volunteer hunters would be called in, Loewen says, in cases where a wildlife officer has determined that a bear must be killed—for instance to protect human life, property of livestock. Hunters will be given 24 hours to show up and begin the hunt.

“This new management tool will see eligible Albertans who have been chosen to participate in the program, contacted by government staff to respond when livestock are being killed, crops are being damaged, for public safety, or other concerns,” Loewen’s staff wrote in an October 22 email.

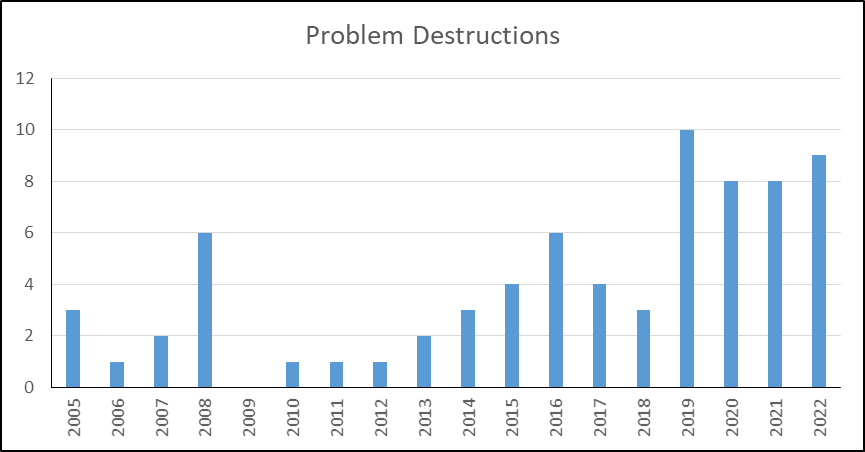

And even though every year only about four grizzlies—a threatened species in Alberta whose numbers have not recovered in accordance with goals set out in 2020—are currently euthanized because of said concerns, Loewen’s new policy has a built-in quota of eliminating 15 bears from the gene pool, representing a potential 375 percent increase in euthanized grizzlies. It’s not a hunting opportunity, the province insists, rather, it’s “another tool to manage problem wildlife by including Albertans as part of the solution.”

But how does having hunters kill problem bears solve anything besides ‘I need a rug for my den’? Problem bears that must be killed are being killed now by officers; switching hunters for officers will affect nothing, except perhaps putting untrained hunters in danger.

Just across the national park border, there are plenty of examples where successful grizzly bear management occurs with no killing required. I recall one afternoon in May of 2015, when my colleagues and I were preparing to release a grizzly bear back into the wild. This particular bear, dubbed G137, had killed a calf in Whistlers Campground, in close proximity to hundreds of visiting campers, and as a result, Parks Canada’s decision matrix—a distillation of many years of research and experience—along with team discussions and consultations with wildlife conflict specialists, concluded that the bear should be trapped and relocated.

In conjunction with grizzly bear expert Gordon Stenhouse, Parks Canada staff trapped the bear without incident and then measured, took samples, ear tagged and GPS collared the grizzly, so we could learn as much as possible from her behaviour after the release.

To our dismay, not long after releasing her approximately 75 kms south of her elk-hunting grounds, the bear started heading north, straight back to town. After about three days, she was in the vicinity of the campground again, pretty much exactly where we didn’t want her to be!

But then, instead of re-establishing herself amongst the campers, G137 kept on going. She moved along the slopes of Signal Mountain, then turned into the Maligne Valley, where she spent the remainder of the summer, bothering no one. It was a successful conflict resolution, with no shooting required.

A happy ending isn’t always in the cards, of course. Sometimes, if a bear has become so accustomed to people and human food that it becomes aggressive and refuses to leave ‘no go’ zones of high human density, euthanasia is necessary. Before that step is taken, however, deterring or translocating problem bears are the preferred management tools. As a result, over the last 23 years, only three grizzly bears have been euthanized in Jasper National Park, or about 0.1 bears per year.

This approach is very much in contrast with the new strategy Alberta is apparently hell bent on taking. Farming out the dangerous task of killing problem bears to private citizens will increase, not decrease, the risk to humans; allowing an extra 24 hours to call in a hunter will increase, not decrease, the response times to wildlife conflicts; and facilitating the volunteer harvester will, in most cases I can fathom, only increase, not decrease, the workload for wildlife officers.

Improving human/bear management techniques will reduce conflicts, but simply subbing in some trigger puller with unknown experience to do the work of a qualified wildlife professional will not.

While it’s fairly easy to poke holes in the province’s predicted outcomes, a bigger question remains: What led the province to think there is a problem that needs fixing in the first place? Minister Loewen has stated that the number of bears has increased, and those bears have been causing more problems. But determining how many grizzly bears there are in Alberta is not at all straightforward.

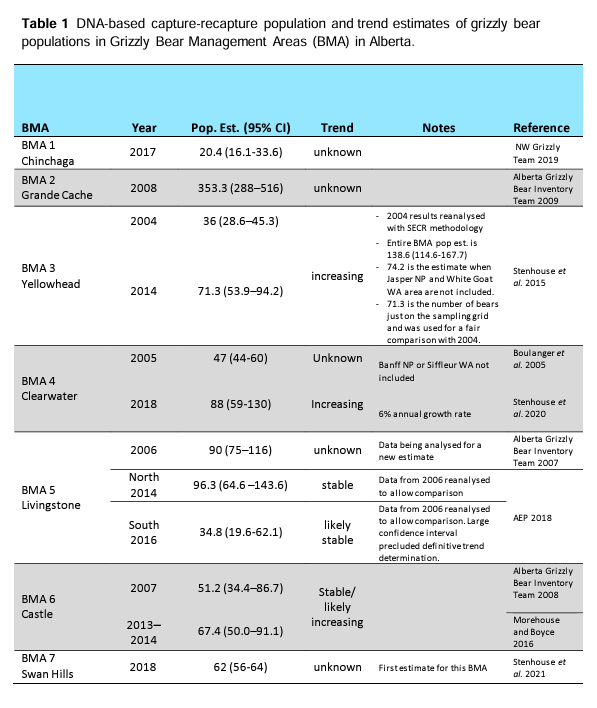

For one, the province is too big to simply count up how many grizzly bears are in it at one time. There are seven bear management areas in Alberta, all censused in different years, and grizzly populations in three of those areas have only been estimated once (meaning a trend cannot be determined). Moreover, of the four areas that have been censused twice, only two have increasing bear populations (a 76 bear increase over about 10 years). If you add up the most recent population estimates, you get 803 bears throughout Alberta, not including Jasper and Banff. Without offering an explanation for the sudden appearance of hundreds of more bears (there have been no population estimates since 2018), Minister Loewen has claimed in the media that there are now 1,150 bears in the province.

The minister also claimed that there are about 20 problem bears killed per year, yet according to the most recent data listed on the Alberta website, since 2005, only 4.2 bears are destroyed per year.

If the need for change to the status quo in Alberta is not obvious due to lack of current information or reporting, and the predicted outcomes are “iffy” at best, then why is the province resurrecting what certainly looks and sounds like a grizzly bear hunt?

Could it be that the province doesn’t believe in its own Grizzly Bear Recovery plan? Could it be that Loewen truly thinks that by reducing bear numbers, we’ll be reducing the number of people killed?

Or could it have something to do with placating those who the minister claimed to have informally consulted with: not his own scientists, not the general public, not Indigenous communities, but “rural Albertans” whose votes helped usher in a UCP victory in May?

If that’s the camouflage with which Minister Loewen is trying to disguise a revived trophy hunt of “problem” wildlife, I’ve got news for him: his intentions are in plain sight.

Mark Bradley // info@thejasperlocal.com