Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article said the caribou breeding facility had a $14 million budget. The budget has been increased significantly since that number was first reported and as of October 3, 2023, the investment from the federal government was $38.2 million. Parks Canada has said “costs may increase given the rapid increase in material cost, inflation, labour shortages and supply-chain challenges.”

Iyleene Joachim remembers when there were lots of caribou in the mountains.

Joachim is an Elder with the Kelly Lake Cree Nation. Joachim’s father was born in what’s now called Jasper, but when he was a child, the family was evicted from the area to make way for the new national park.

Prior to the establishment of Jasper Forest Reserve in 1907, a diverse community of Indigenous and Métis People were forcibly evicted by the Canadian government. // Aseniwuche Winewak Nation

“My grandparents were kicked out of Jasper,” Joachim said

Before they were forced to relocate—an arduous journey across mountain passes, rivers and through all four seasons—Joachim’s grandparents, she says, used to travel by horseback from their home in the Athabasca River Valley, all the way to near McBride, B.C., to harvest salmon from the Fraser River.

“They used to go travelling through the mountains,” she said.

Back then there were many caribou, Joachim said. She remembers them from when she grew up. She remembers them being in the Grande Cache area. But there aren’t many now.

“They’ve disappeared,” she said.

Sightings of caribou, such as these members of the Little Smoky herd, spotted in 2019 near Grande Cache, are becoming more and more rare. // Eddy Dostaler

Elder Joachim is 80, but as she walked around a muddy construction site September 28, she was nimble and sure footed. Around her were caribou scientists, engineers, project managers, communications specialists, construction superintendents and media members. Some of them noticed her take a wide step over a gap in the wooden framing of one of the buildings. She did so ably.

“It must be all the time spent outside,” Shelley Calliou, Joachim’s niece, also from Kelly Lake Cree Nation, offered.

Iyleene Joachim (centre), remembers when caribou were plentiful in the mountains. She, along with other Indigenous Partners of Jasper National Park, were invited to tour the under-construction caribou breeding facility 30kms south of the Jasper townsite. // Bob Covey

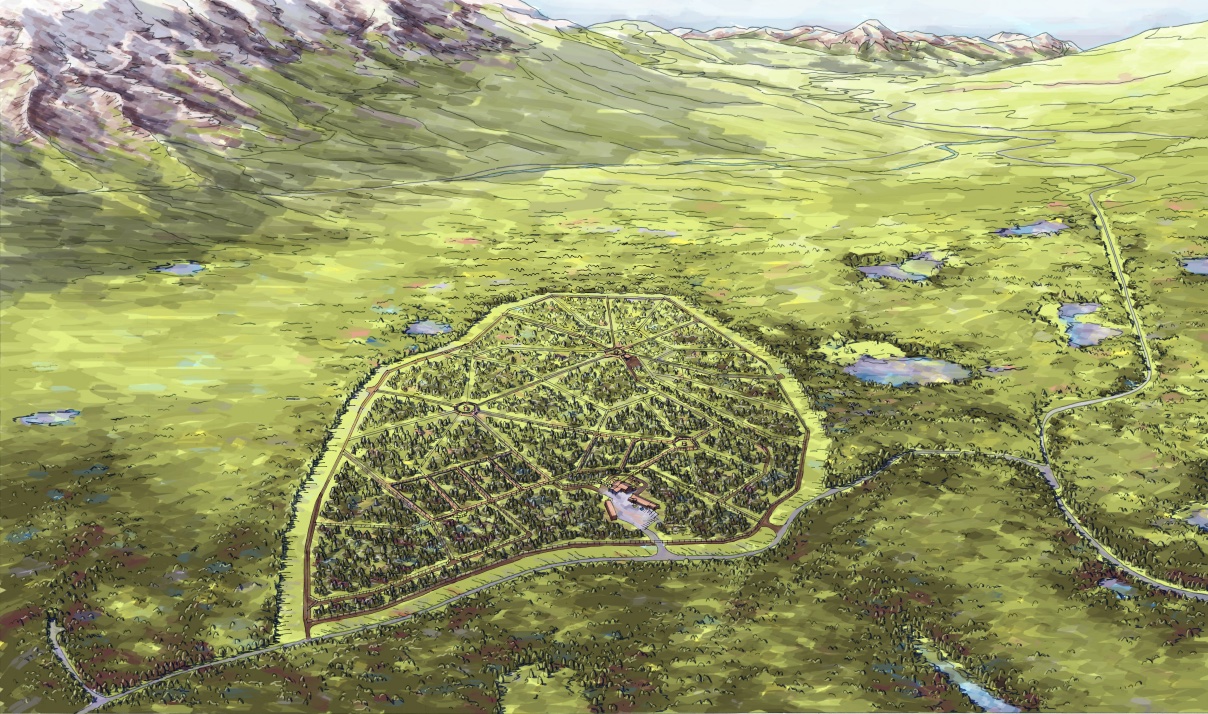

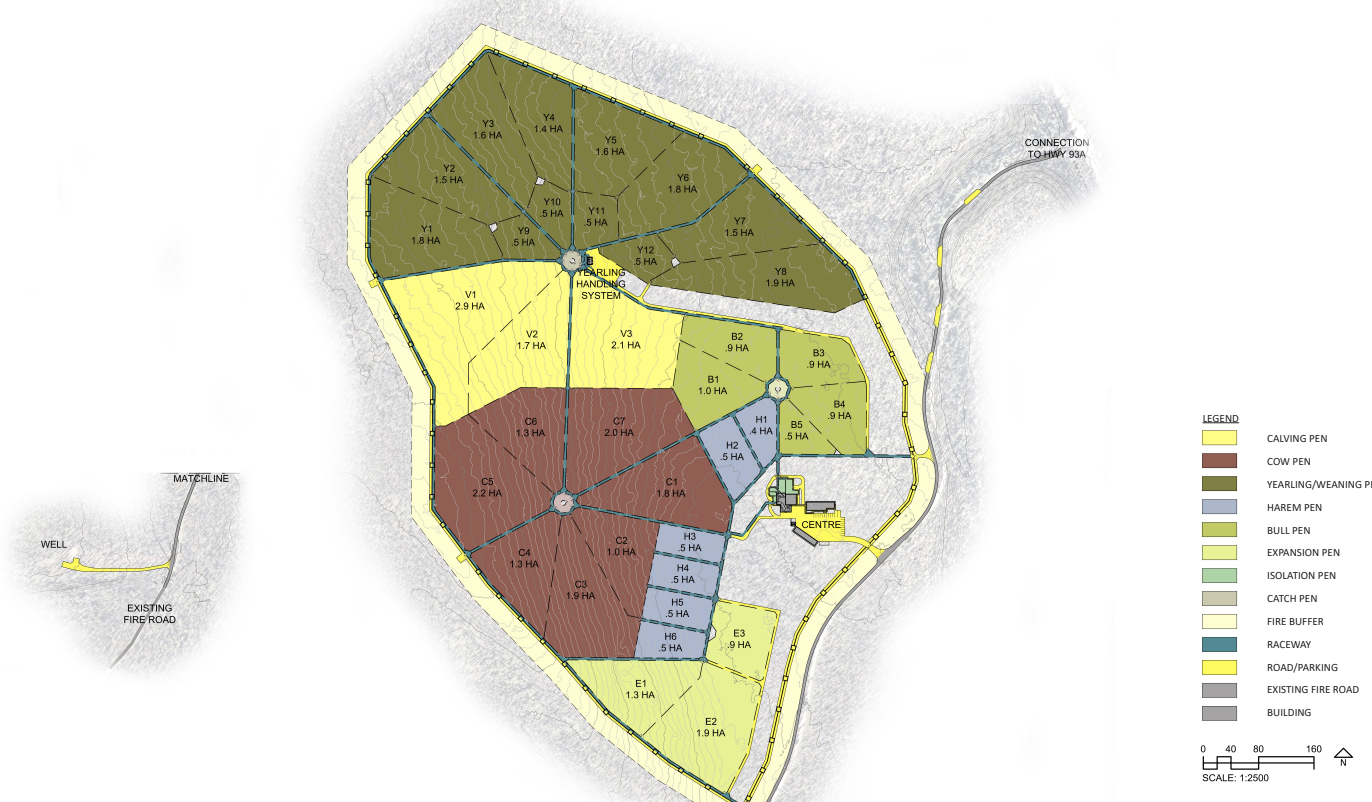

The group was touring a first-of-its-kind caribou captive breeding facility being built 30 kms south of the Jasper townsite. There, the pine beetle-killed forest has been cleared. Building foundations have been poured. Walls have been framed. On September 28, six Indigenous Partners with the project were escorted up Jasper National Park’s Geraldine Lakes Fire Road, partly to get an update on the $38 million facility, which in 10 years Parks Canada hopes will have released 200 new caribou into the endangered Tonquin herd, but also to harvest medicine from the land before the 65 hectare site is overhauled for the conservation project.

“The project is on schedule and on budget,” said the caribou recovery program’s senior project manager, Joshua Kummerfield.

Joshua Kummerfield is the senior project manager of Parks Canada’s caribou recovery program. He helped give a site tour of the breeding facility, which builders project will open in 2025. The landmark project aims to repopulate Jasper National Park’s Tonquin Valley with 200 caribou by 2032. // Bob Covey

Kummerfield and JNP’s caribou recovery program manager, Jean-François Bisaillon, showed the Indigenous Partners where the maternity pens will be located; noted the guiding design philosophy of the program is to keep the places where the captive caribou will live “as wild as possible;” and explained that up to 120 caribou will live at the facility at a time. As heavy machinery rolled by and chainsaws buzzed in the distance, near the back of the group, Frank Roan nodded thoughtfully.

Parks Canada’s $38 million caribou conservation facility is scheduled to open in 2025. Concrete foundations and underground utilities for the three buildings are nearly complete. // Bob Covey

Roan is from Smallboys Mountain Cree, a remote community on the north shore of the Brazeau River, on the Rocky Mountain’s eastern slopes. The caribou which make up the Brazeau herd has been whittled down to less than 12 animals today—a number too small to self-sustain. But Roan, like his auntie from Kelly Lake, also remembers the caribou when they were plentiful. From behind his dark glasses, Roan’s eyes light up when asked about the endangered species. He, for one, wants to see caribou flourish. He remembers when they were harvested—for their meat and hides, but also for the medicine in their antlers and hooves, he said.

Frank Roan, from Mountain Cree (Smallboy) Camp, on the Rockies’ eastern slopes, wants Jasper National Park’s caribou recovery program to flourish. “The direction Jasper is moving in allows inclusion, which is a first for a lot of First Nations,” he said. // Bob Covey

“I would like for that herd to rehabilitate and prosper,” he said. “This animal is significant to us.”

What’s also significant to Roan and other Indigenous Partners, he said, is the way Jasper National Park is approaching the landmark conservation project. Set out in the park’s 2022 management plan are objectives directly supporting Indigenous reconciliation. One of those targets is incorporating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into conservation actions. On the ground at the caribou breeding site, that’s meant consulting on handling and capture techniques, assisting with predator monitoring, and procuring the services of the Aseniwuche Development Corporation to remove dead and overstory pine trees, for example.

And it’s also meant making room for traditional protocol—such as being able to harvest, and prioritizing ceremony. The actions by Parks Canada are important—and overdue— acknowledgements of Indigenous communities’ inherent knowledge, according to Shelley Calliou, from Kelly Lake Cree Nation.

Fred Sowan, Karen Sowan, Iyleene Joachim and Shelley Calliou, from Kelly Lake Cree Nation, were invited to tour the under-construction caribou breeding facility on September 28. The group also practiced a traditional plant harvest before the 65 hectare site is further disturbed. // Bob Covey

“It’s important to be back here because of the expropriation when the park was created,” Calliou said.

Joachim, whose family was evicted from the area now known as Jasper National Park before she was born, recently taught her grandson what a caribou print was. He had never seen one before. It’s possible that the caribou recovery project could change that. That makes her happy, she said.

“Not that long ago we weren’t allowed at the table,” Roan said. “But our knowledge and our way-of-life has existed in this land for time immemorial.

“Now our insights are acknowledged.”

Bob Covey // bob@thejasperlocal.com